Without urgent action on climate change, the conditions that underpin the health and well-being of the human population will be greatly diminished in coming decades, and may only be available to a small number of people living in a few parts of the planet by the end of this century.”

Professor Peter Doherty, Nobel Laureate

Melissa Sweet writes:

Federal, state and territory governments should establish a Ministerial Health and Climate Change Forum to oversee coordinated national action to tackle the urgent health threats arising from climate change, according to a landmark report released this week.

It recommends that the Forum include Ministers from each jurisdiction whose portfolios cover health, energy, the environment, resources, emergency services, planning and infrastructure.

The report, developed by the Climate and Health Alliance with wide consultation across the health sector, sets out a detailed road-map for addressing the health risks of climate change. It is aimed at the health and other sectors that influence the determinants of health.

The Framework for a National Strategy on Climate, Health and Well-being for Australia, with a foreword by Professor Peter Doherty (as quoted above), was released in Parliament House in Canberra on Thursday.

It calls for a national educational campaign to inform communities about the health risks of climate change, health-protective adaptation strategies and the health benefits of reducing emissions and transitioning to a low carbon future.

The framework also recommends a national certification and labelling scheme for products to guide consumers towards low carbon choices.

It calls for a national education and training framework to support health professionals in recognising, preparing for and responding to the health impacts of climate change, establishment of a national sustainable healthcare unit within the Federal Health Department, and an end to subsidies for fossil fuel based energy industries.

The framework recommends health impact assessments as part of evaluations of applications for changes in land use, and says climate risks should be evaluated as part of health policy development at local, state and federal levels.

It also calls for the NHMRC and Medical Research Future Fund to establish climate change and health funding streams.

The report is a landmark development for many reasons, not least the urgency and scale of the health challenges arising from climate change, which stand in stark contrast to the lack of leadership to date from the Federal Government and its health agencies.

It speaks volumes that the extensive consultation and detailed recommendations of the report reflect the work of a small, poorly resourced organisation (CAHA) and volunteers, rather than central health agencies with massive budgets.

However, the tripartite support for the framework’s launch is significant, and Indigenous Health Minister Ken Wyatt’s supportive comments clearly indicated a real concern for the wide-ranging health impacts of climate change.

Shadow Health Minister Catherine King pledged that a Labor Government would draw on the framework in implementing a national strategy on climate, health and well-being, while Greens leader Senator Richard Di Natale echoed King’s comments that the document offered sensible advice for ways forward.

The report’s release was timely, following hot on the heels of the release of Disaster Alley: Climate change conflict & risk, by Ian Dunlop, a former oil, gas and coal industry executive, and David Spratt, Research Director for Breakthrough and co-author of Climate Code Red: The case for emergency action (Scribe 2008).

According to this report, the world now faces existential climate-change risks that may result in “outright chaos” and an end to human civilisation as we know it. It argues that Australia’s political, bureaucratic and corporate leaders are abrogating their fiduciary responsibilities to safeguard the people and their future well-being.

It says global warming will drive increasingly severe humanitarian crises, forced migration, political instability and conflict, and warns that the Asia–Pacific region, including Australia, is considered to be “Disaster Alley” where some of the worst impacts will be experienced.

It says global warming will drive increasingly severe humanitarian crises, forced migration, political instability and conflict, and warns that the Asia–Pacific region, including Australia, is considered to be “Disaster Alley” where some of the worst impacts will be experienced.

“It is essential to now strongly advocate a global climate emergency response, and to build a national leadership group outside conventional politics to design and implement emergency decarbonisation of the Australian economy,” the report states.

In many ways, the framework developed by CAHA is an exemplar of this – civil society providing leadership where conventional governance has failed.

The CAHA report notes that policies and frameworks to address climate change and health have been developed by the EU and in the US by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, while the UK has implemented a policy for the NHS that includes both mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Recommendations

Principles underpinning the CAHA framework’s recommendations include the need to take a health in all policies approach, that environmental protection is a foundation for health and wellbeing, and that Indigenous rights, wisdom and cultures must be central to policy development on climate mitigation and adaptation policies.

The Framework states that its recommendations would help the Federal Government meet its international obligations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Paris Agreement, the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights and its commitments to the Sustainable Development Goals.

The document addresses seven areas of policy action, including health-promoting and emissions-reducing policies, where recommendations include developing programs and incentives to encourage low emissions active and public transport, to encourage uptake of electric vehicles and low and zero carbon, climate resilient buildings and infrastructure, including in the health sector.

In the policy area of emergency and disaster preparedness, recommendations include investing in identifying and mapping vulnerable populations and infrastructure to inform climate adaptation strategies and emergency response plans.

In the area of supporting healthy and resilient communities, the recommendations call for community based health and social organisations to be resourced and supported to develop their understanding of climate risks to service delivery and the populations they serve, and for recognition that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are particularly vulnerable to the health impacts of climate change.

In the area of education and capacity building, the strategy calls for all undergraduate and relevant postgraduate health and medical curricula to incorporate content addressing the health challenges of climate change.

For policy action regarding leadership and governance, the report calls for Australian health representation at international climate forums, including sending health delegates to represent Australia at the annual UNFCCC climate talks and the annual WHO Climate and Health Summit.

For policy action to ensure a sustainable and climate-resilient health sector, the framework calls for a national sustainable healthcare unit to be established within the Commonwealth Department of Health to provide leadership and direction to the health sector, and for mandatory standards prioritising climate resilience for health facility design, construction and ongoing management.

Regarding policy on research and data, the report calls for a national environmental health surveillance system to be established that includes climate-related indicators.

A political launch

At the Parliament House launch, CAHA executive director Fiona Armstrong described the process leading to the framework’s development, including a global survey in 2015 that found Australia was lagging behind comparable countries in tackling the health impacts of climate change.

Without such a national strategy or a mechanism to include health in climate policy decisions, Australia would fail its obligations under the Paris agreement, she said.

While Commonwealth leadership on climate and health was required, there was also an onus on state, territory and local governments as well as the wider health sector, which is responsible for 5-10 per cent of national emissions, she said.

Armstrong stressed the importance of cross-sectoral action: “This is a complex problem and solving it silo by silo simply won’t cut it.”

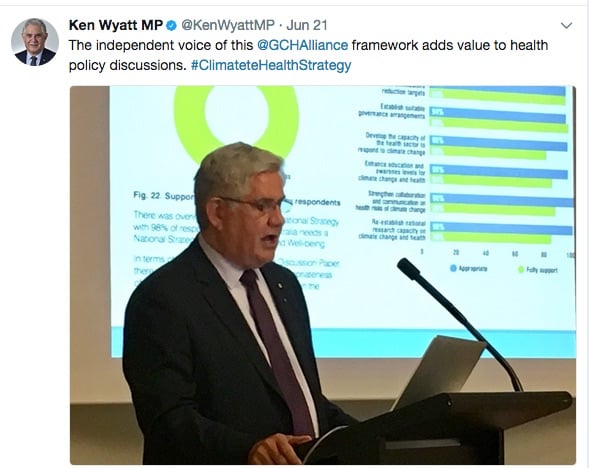

Minister Ken Wyatt congratulated CAHA for providing “this important report”, and said he would discuss it further with Health Minister Greg Hunt.

Minister Ken Wyatt congratulated CAHA for providing “this important report”, and said he would discuss it further with Health Minister Greg Hunt.

“The independent voice of this strategy framework adds value to policy discussions,” he said.

Wyatt acknowledged that the Federal Government and Federal Health Department had a role in responding to the health impacts of climate change and related disasters and emergencies, and cited evidence from the World Health Organization about the global health impacts of climate change.

He vividly recalled seeing a presentation, during his period working in NSW Health, about the impacts of rising temperatures, and said that the presentation had left “an indelible impression”.

Wyatt said the Commonwealth Government assumed overall responsibility for the national perspective on health and climate change, and described a number of relevant policy areas (read his full speech here).

Catherine King committed a future Labor Government to developing a climate health and well-being strategy based on “the terrific work” of the framework.

“The science of climate change is not accepted by everyone in this Parliament or everyone in the Government,” she said.

“The unfortunate reality is that we will struggle to address this global challenge while we are still fighting what my colleague Mark Butler in his new book has called ‘The Climate Wars’.”

Senator Richard di Natale, a doctor, congratulated all who contributed to this “excellent” piece of work advocating for a national framework to support transformation across health systems.

“We are at a critical juncture right now; we know that we are facing catastrophic global warming,” he said.

While Australia’s lack of progress was depressing, he said the news was not all bad, including that President Donald Trump had limited ability to influence what was done in the US because the States there had control of the levers.

“When you look at what is going on globally, there is great cause for optimism,” he said. “Globally, huge changes are occurring; this is a global problem, it requires global solutions and the world is acting.”

Di Natale stressed the co-benefits to health of reducing emissions. He said:

When you transform your energy sector, when you transform your transport sector, when you make sure that you plan your cities in a way that encourages active transport and drives down emissions, you actually produce a range of other co-benefits.

It means reductions in things like heart disease, and obesity, reductions in things like diabetes, and of course road deaths, injuries – and improved air quality.

If we make this transition, we actually ensure that we create a healthier, more sustainable community into the future. Of course if we don’t act, every year we delay action, the cost of inaction grows and the cost to the health budget will grow exponentially.

It’s so critical that we don’t just see climate change as an issue of energy security and energy prices but also as something that directly impacts the health of every single Australian.”

Dr Liz Hanna, president of CAHA and an academic at ANU, gave an alarming overview of the impacts of rising temperature upon health, now and into the future. She said:

The climate science is settled and the residual uncertainties are merely – how bad and how soon?

It’s a human survival issue that we are facing. The health challenges are massive; the health sector needs to be prepared.

It’s not only political will but getting the urgency of the message out to the community so it’s part of every decision they make with their own emissions.”

Watch the interview at the end of this post with Dr Hanna.

What next?

After the launch, the Australian Healthcare and Hospitals Association (AHHA) hosted a round-table discussion. Attendees included Federal Health Department representatives Dr Tony Hobbs, the Deputy Chief Medical Officer, and Chief Nursing and Midwifery Officer Debra Thoms.

Discussions focused on how to disseminate the framework across the health and other sectors and how to encourage widespread engagement and implementation.

Fiona Armstrong told the meeting that CAHA’s success in bringing the three political parties together around such a contested issue reflected the organisation’s strategy of taking a collaborative rather than an antagonistic approach.

The framework was nationally and globally significant, she said, and now was the time to broaden the list of organisations and individuals involved with CAHA and the Our Climate Our Health campaign for a National Strategy on Climate, Health and Well-being for Australia (note to readers: details of this campaign and website were added on 24 June).

Other potential partners identified at the meeting included Primary Health Networks, ACOSS, Universities Australia, health and medical colleges, Oxfam, rural lobby groups, and other sectors, including architects and town planners.

As Federal MPs disperse for the winter Parliamentary break, the campaign is planning to assemble an army of climate and health advocates in the lead-up to the next federal election.

CAHA is urging health professionals to engage with the campaign’s plan to create a climate health mentor for all MPs.

Armstrong said the movement for action on climate and health could not afford to wait for federal endorsement, and she noted that some state and local governments and health services were already seeking to engage with the framework.

Discussions also focused on getting climate and health onto the agenda of health ministers and COAG.

The meeting urged individuals and organisations organising health and social conferences to include a focus on climate and health, and it was noted that the RACP Congress would do this in 2018.

A strong message from the discussions was that the wider health sector now had a responsibility to run with the framework rather than wait for CAHA to drive these processes going forward.

Armstrong said:

It’s an all-in approach. Everyone needs to take some responsibility.

This is a very complex problem, none of us can solve it on our own.

The health sector can bring extraordinary expertise but we need to work together with policymakers, parliamentarians at all levels. We all need to find our niche in terms of progressing it.”

Suggestions for Croakey readers

Drawing on the round-table meeting’s discussions, here are some ways that Croakey readers could engage, whether as individuals or organisations:

• Write to health, energy and environment ministers endorsing the framework and asking them to respond

• Ask your organisation’s members to meet with their MPs

• Sign up to mentor politicians in how they might advocate for a #climatehealthstrategy in Parliament

• Check out the advocacy tools and resources to support this work

• Talk to policy makers, and health department representatives to ask what they will do to adopt the strategy

• Host a meeting or event or have a session at a conference

• Approach other organisations asking them to support

• Donate to CAHA’s work

• Use the CAHA logo on your website or your social media profile, indicating your support

• Engage with media and social media on climate and health

• Use the CAHA resources including postcards, posters, and badges for your websites

• Provide feedback on the framework

• Implement elements of the framework

• Write about the framework in your publications and journals.

The meeting concluded with applause and congratulations for Fiona Armstrong, acknowledging her immense contribution and commitment to climate and health advocacy and policy. “Australia is the better for you,” said Hanna.

Watch this interview

Dr Liz Hanna has been researching climate change and health at ANU for the past 10 years with a focus on the health effects of heat and the looming health crisis this is presenting for Australia. She calls for everyone to engage with the recommendations of the report – not only policymakers.

“We are talking about survival of the species,” she says. “This is bigger than politics. We are not politically motivated… we seriously just want some decent policies…”

#Selfies

Further reading

Further reading

- The Guardian’s report on the launch

- Analysis of the draft strategy

- Our archive of stories on climate and health

- The #JustClimate archive